(by Jeremy Holmes of The Aquinas Institute)

This past July, the Albertus Magnus Center Summer Program spent two weeks reading the Aquinas Institute’s latest volume, Book IV, Distinctions 1-13 of St. Thomas Aquinas’s Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard. Not many students have had the opportunity to read Aquinas’s Commentary at length. We asked AMCSS Vice-President Christopher Owens to tell us how it went.

First, tell us a bit about the Albertus Magnus Program.

The Albertus Magnus Center for Scholastic Studies promotes renewal in sacred theology according to the mind and method of the great scholastics, and particularly the work of St. Thomas Aquinas. We achieve this primarily through our annual summer program held in Norcia, Italy in cooperation with the Benedictine monastery there.

During the two-week program we follow a seminar method, looking to the great masters as our teachers. In addition, we have daily lectures by the tutors, the Fathers of the monastery, and other guest lecturers. The program culminates in a scholastic disputation and magisterial response, which allows for a synthesis of the materials learned and an application to contemporary questions, engaging theological questions of our own time and so contributing to the common good of the life of the Church.

Why was St. Thomas’s Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard chosen for this year’s program?

Over the last three summers we worked through several of Aquinas’s commentaries on the Pauline epistles, and before that we undertook systematic readings of various parts of the Summa. We wanted to change things up a bit this year. We have been friends with the faculty of the Aquinas Institute for a decade or more, and have been looking forward to the publication of the Sentences Commentary since the inception of the project. We were especially excited about the possibility of making a systematic study of the Commentary for the first time in English with recourse to the Latin text.

Did many attendees have previous experience with the Commentary on the Sentences?

We were privileged to have present the Aquinas Institute’s own Dr. Peter Kwasniewski, whose translations of selections of the Commentary on Love and Charity was published by CUA Press, and I have worked on medieval commentaries on the Sentences. We also had two doctoral students who are engaged in some exciting research on medieval theology. This was a great benefit to the seminar, but lack of experience was in no way an impediment for those who had never studied the Sentences commentarial tradition. Indeed, it was refreshing for me to hear of discoveries in the text from those who had never been exposed to the method.

Inevitably, people compare St. Thomas’s earlier Commentary with his later masterwork, the Summa theologiae. Did points of comparison come up in class? Does the Commentary have any unique advantages?

Fr. Torrell reports that St. Thomas would have been less than 30 years old when he was writing this first Commentary, while the Tertia Pars of the Summa would have been much later — indeed, when Thomas died, he left his treatise on the sacraments in the Summa unfinished. There is a great benefit to looking at the whole of Thomas’s career in order to try and discern a development in the thought of Thomas from his youth to his maturity. This historical approach can yield great insight—for example, Fr. Reginald Garrigou-LaGrange’s defense of Thomas’s belief in the Immaculate Conception depends upon not only reading the Summa, but his Sentences commentary, and other works.

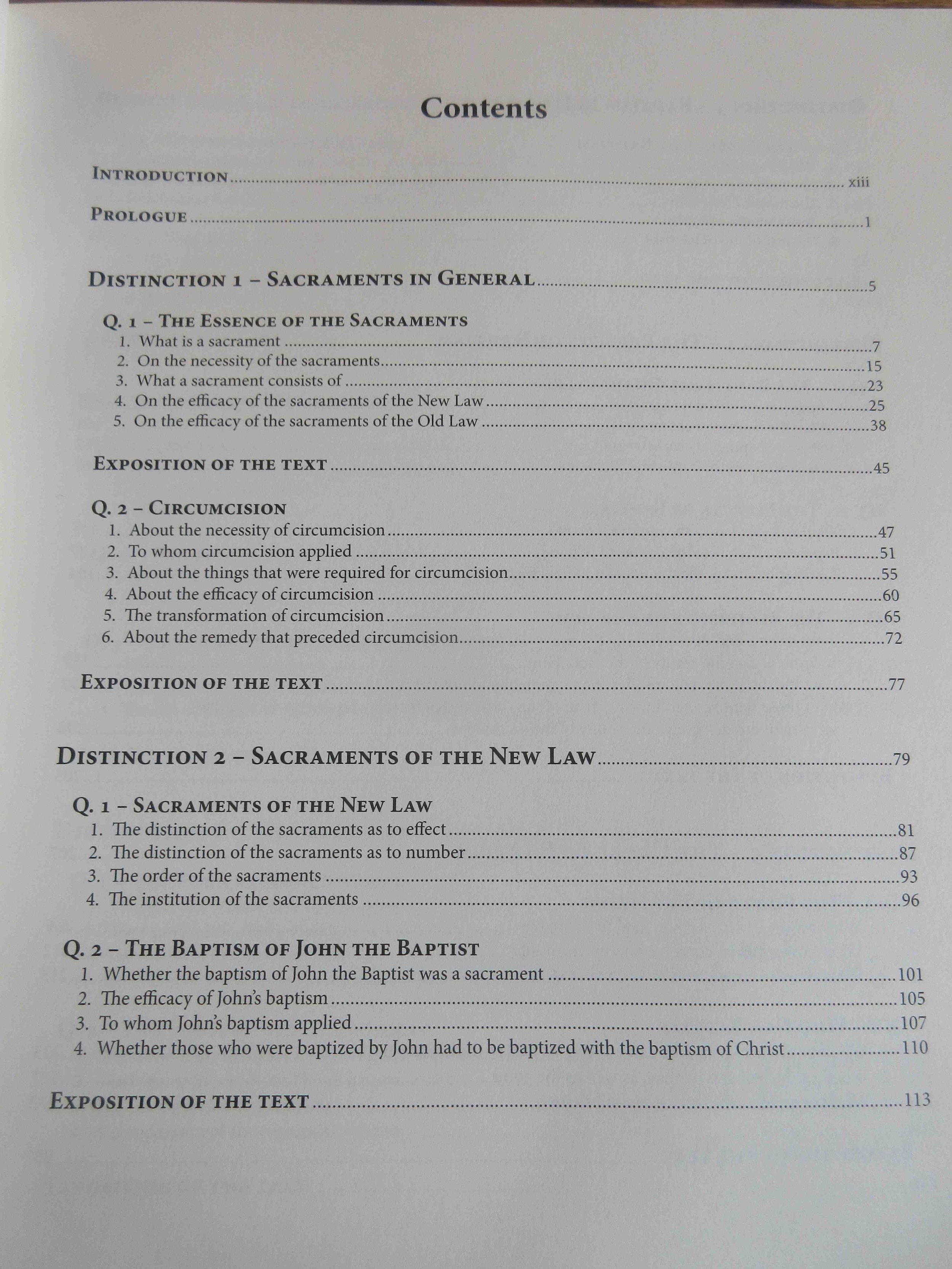

However, we made a decision early on that such an attempt would be futile for the seminar: we simply never would have gotten through the work. Although there were occasional references to the Summa during our seminar study, on the whole what we found is that the text, and particularly the methodology of the text, stands as worthy of engagement on its own. Since our goal is not only to know what Thomas thinks about a particular issue, but more importantly what the truth of the matter is, Thomas’s methodology in interrogating the question opens up the subject for the reader to see the many facets of the issue under dispute, and allows the student to arrive at his own insights. Indeed, the Sentences Commentary uniquely opens up to the reader the breadth and depth that a particular question may have, since rather than a standard three objections, as one might find in the Summa, there will at times be as many as a dozen or more objections and counter-objections put forward in one question.

The unfamiliar format can be intimidating to a newcomer, but the Aquinas Institute edition is a great aid. The page headings make it easy to find the various distinctions, questions, articles, and quaestiunculae. The text itself is beautifully printed with a minimal amount of mark-up, but enough to help make the edition truly usable as a bi-lingual research tool. The quality of the binding is wonderful, and this is particularly important with such a large text. The text is footnoted both with critical remarks about the text or translation and also cross-references for further research.

Did your impression or imagination of St. Thomas change through your immersion in his early work?

In so many ways, yes! But here, I will constrain myself to two observations. First, perhaps the most unfortunate characterization of scholasticism by some mid-20th century theologians is that it is devoid of the vitality of the Spirit which is present, for instance, in the Patristic era. Reading Thomas’s Commentary, one cannot help but see that this characterization is manifestly false. My experience of reading the Commentary was that I found in the text to be an intensely personal search for Christ and his truth, one which enlivened my own heart and mind through following in the footsteps of Aquinas.

Second, even in schools today where St. Thomas’s Summa is considered an authority in the classroom, it can sometimes be taught not theologically, but rather as if it were the Catechism (albeit a much more detailed catechism). But to do this, I think, is to miss the point of the scholastic endeavor entirely! In reading the Sentences Commentary, the learner is put back in touch with the fact that this text is theology: it is faith seeking understanding; it is one theologian entering into dialectic with other theological opinions of his day, and trying to work out what is the truth. In this, we are reminded that theology as a sacred science is first of all about divinization, for it is the science of God and the Saints. Thus, here below, theology is about working out our faith, personally and ecclesially. The Commentary on the Sentences offers to the reader a most excellent guide to this process, both in providing some answers, but perhaps more importantly in providing a model for the right way to ask questions.

How would you envision the Commentary being used in a university classroom? In large sections on its own, as in the St. Albert the Great Program, or in smaller selections in connection with the Summa, or in some other way?

This is certainly a difficult question! As far as I am aware, in those faculties where specialized studies are offered in the theology of Thomas Aquinas, the Sentences commentary plays an ancillary role in the Thomistic curriculum. But this is not the fault of the faculty: up to now, there has not been a widely available edition for student use, even for those students who have facility with Latin. Thus, the new Aquinas Institute editions create opportunities to explore the rich theology contained in these rarely used texts. I hope that we will see elective courses dedicated to the study of the Commentary cropping up all over the place now that there is a quality edition available. In addition, these new editions could be used as a foundation for graduate studies in sacramental theology for a class on medieval thought; or else, portions of the text would be highly beneficial in support of a greater understanding of the Eastern and Western disputes over the sacraments.

Another consideration, one which might challenge a paradigm, is that we might rediscover the practice embodied in Aquinas’s Commentary. While the commentary tradition is all but absent from today’s theological curriculum, commentating on the Sentences of the Lombard was considered the foundation of high scholastic education, and it offers a unique way to compare the thought of different theologians: they all start from the same text, and then have points of convergence and divergence. A widespread re-discovery of this methodology might offer a challenge to the way theological disputation is undertaken in the 21st century. It might even provide a vehicle for resolving contemporary disputes, which too often suffer from a vastly disparate set of sources and methods in coming to opposed conclusions.

Who is eligible to participate in one of your two-week summer programs?

While our program is academic in nature and pitched at a graduate level, many participants come for a time of retreat and relaxation, and sometimes vocational discernment: Br. Augustine, OSB (the brewmaster at the monastery) was a participant in our first summer program, and we regularly have priests who join us for their two-week vacation from parish life. Monastic chant, the majestic Sibilline mountain range, and traditional Umbrian cuisine create an ideal setting for contemplation of higher truths. We have hosted doctors, businessmen, school teachers, attorneys, and even retirees, with attendees from Chile, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Italy, England, and the United States. Although we are non-accredited, we have usually been able to make arrangements for a student’s home university to offer some sort of credit for their participation in the program.

What’s up next for the St. Albert the Great Program?

This past year was the first year that we held the program near the new monastery on the mountain outside of Norcia. The agriturismo where we stayed was a great hit, and the nightly five-course meals were incredible! Just as we published last year’s proceedings, so we intend to publish the proceedings from this past summer’s program, hopefully in time for Christmas. Plans are underway for next summer’s program on Divine Providence and Human Suffering, using the Aquinas Institute’s edition of Thomas’s Commentary on the Literal Sense of Job as our primary text. We have confirmed that the dates for next year’s program will be during the last two weeks of June. We will be launching details about the program, as well as opening the application process, on this coming St. Albert’s Day (Nov. 15th). We hope to fill the agriturismo, so please do spread the word, and get in touch if you’d like to help us out in some way.

How can people find out more?

Please, feel free to visit our website or else drop me an email!