The Life and Times of the Universal Doctor

/Irven M. Resnick and Kenneth F. Kitchell, Jr. Albertus Magnus and the World of Nature. Medieval Lives. Chicago: Reaktion Books, 2022. 224pp., hardback; $22.50.

It was many years ago when I first learned about the android of St. Albert the Great. It is recorded, among other loca, in the oh-so-reliable Supplement to Mr. Chambers's Cyclopædia: or, Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, published in 1753:

One sighs upon seeing that Mr. Chambers’s cited authority is Bayle, yet, thankfully, the truth about the life of the teacher of the Angelic Doctor has been told by others (e.g., see Sighart, Schwertner, O.P., Albert, O.P., or Vost), and scholarly attention has treated of his theological, philosophical, and natural scientific work (e.g., see Resnick, ed., as well as Weisheipl, O.P., ed.). Irven Resnick and Kenneth Kitchell’s Albertus Magnus and the World of Nature stands in both camps, telling the true story of the Universal Doctor’s life and work as a keen observer of the world of nature and its creatures, including the human. (It is the least done by the book to note the legendary nature of the above encyclopedic entry (214 and n1), a tall tale that continues to garner academic attention in our age of “AI” more truly frightful than Albertus’s imaginary androides.)

This is not the first time Resnick and Kitchell have joined forces on the subject. Their previous works include St. Albert’s Questions concerning Aristotle's On Animals, his zoological works in Albertus Magnus On Animals: A Medieval Summa Zoologica, volume 1 and volume 2, and Albert the Great: A Selectively Annotated Bibliography (1900-2000). (Resnick has also translated the saint’s On The Causes Of The Properties of the Elements.) Their long experience and deep expertise in this area is evident as they give the reader an endlessly fascinating and magisterial tour of “Boots the Bishop’s” life devoted in no small part to the study of the wonders of creation. Examples flow almost endlessly—some surprise, others even shock.

The book is divided into two parts: the first four chapters treat of the life of St. Albert, while chapters five through eleven consider his work in the study of nature and the “legend and influence” it has had over the past eight-hundred years.

A LIFE ACCORDING TO GRACE SPENT IN NATURE

The first chapter treats of what is known about Albert’s early life and his entry into the Dominican order. Living in Cologne at this time is set into relief with a discussion of his early works, interaction with Cologne’s Jewish community, and his graduation to lector on the Sentences. The second chapter finds the master-in-training in Paris, treating of Albert’s medieval context: the relatively recent Aristotelian renaissance, the mendicant controversies, and the academic life of the university of Paris. Resnick and Kitchell devote most of the chapter, however, to the 1248 condemnation of the Talmud in Paris, considering Albert’s part in the proceedings and his career interaction with the Jewish tradition. The chapter closes with Albert meeting Thomas and the two departing for Cologne.

The third chapter describes his work at the studium generale where Aquinas studied philosophy, including Albert’s progressive introduction of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. The authors limn the scope of “Albert’s Aristotle Project” to paraphrase and comment “on the entirety of Aristotle’s philosophical and scientific work available to him in Latin.” (66) This work occupied about twenty years of the saint’s life, through his travels and time as magister, prior, and bishop. His thought—given the proscription of Aristotle’s natural philosophical works “until purged of error”—was “how could they be purged of error if scholars did not investigate them. Albertus clearly established this as a principal goal: to investigate and rehabilitate Aristotle for a Christian audience,” which included his eager Dominican brethren (68). Detailing his service to the Church as prior, the third chapter closes within sight of Albert’s consecration as bishop of Regensberg in 1260.

Once a bishop, he continued to comment upon Aristotle and the Scriptures; his travels to visit parishes earned him the nickname “Boots the Bishop” (episcopus cum bottis, or episcopus cum magnis sotularibus). The book includes an appendix describing and calculating Albert’s lifetime of travels, just north of 19,000 miles. His episcopacy is short: he resigns in 1261, eventually returning to teach in Cologne from 1270 until the end of his life, his mind and memory failing him in his old age (the Blessed Virgin Mary’s promise, told as a pious story earlier in the book, was fulfilled). His generous bequests in his will (a papal dispensation when bishop allowed him to receive a pension), his frequent interventions as peacemaker and arbiter, and the overall force of a life well-spent are all deftly told.

ALBERT’S MEDIEVAL ZOO

The fifth chapter sets the stage for the in-depth accounting of Albert’s work as a naturalist. We are introduced to the ancients who studied the natural world, from the Greek age (Aristotle and his commentators) and the Roman era (Plutarch, Seneca, Pliny) to the translations which brought them all to St. Albert’s library. We read of the old “experts” in nature, folkloric and “logographic,” as well as twisting and turning translation and mistranslation that morphs crab claws into crab lips and grow giant, elephant-drowning worms in the river Ganges.

This voluminous but mottled traditio of natural folklore enters into the “encyclopedic” age of the 13th century through the work of Isidore of Seville or Rabanus Maurus and, as described in detail in chapter six, is then compiled and collated by Alexander Neckam, Thomas of Cantimpré, Bartholomew the Englishman, and Vincent of Beauvais. In this “golden age” of the medieval encyclopedist, their works “began to emphasize the natural laws and principles at work in the world” and, not organized as modern reference works, “expected their readers to explore the whole of the text, just as they hoped to provide a window onto all things capable of being known. Their principle of organization was typically indebted to Plato and Aristotle, then, and introduced a philosophical rather than biblical division of the world.” (120) The encyclopedists, as it were, served as the first popularizers of the new science made available from Graeco-Arabic sources. One is reminded of Lewis’s description that, “at his most characteristic, medieval man was not a dreamer nor a wanderer. He was an organizer, a codifier, a builder of systems. He wanted ‘a place for everything and everything in the right place’. Distinction, definition, tabulation were his delight.” (The Discarded Image, 10) St. Albert, however, “was not merely a compiler. He was himself as original thinker who sought to extend the boundaries of human knowledge through his own scientific observations of the natural world.” (129)

Indeed, as St. Albert writes in his commentary on Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics, “Of the demonstrative sciences, not all are finished, but many things as yet remain to be discovered” (my translation; Opera Omnia, vol. 2, Borgnet ed., p. 3: “[S]cientiae demonstrativae non omnes factae sunt, sed plures restant adhuc inveniendae”). This line, from St. Albert’s commentary on the first book of Aristotle’s treatise on the logic of scientific discovery, is in answer to an objection that Aristotle’s logic is useless given the current “accomplished” state of knowledge.

Thus, in the seventh chapter, “Albertus and the Experts,” we learn of St. Albert’s methods to more fully finish the sciences of nature. Whether building upon or criticizing earlier works from Aristotle, Avicenna, Pliny, and others, St. Albert either does the experimental work himself or finds, builds, maintains, and avails himself of a network of experti, experts in the field with their own experience. This thoroughgoing dialectic of experience is set forth in great detail with a wealth of examples. We follow St. Albert as he dissects moles’s eyes, tests scorpion salves, decapitates cicadas to see if they can still sing or if salamanders and spiders resist fire. He tests whether—as “some” have said—wax makes salt water fresh, if ostriches eat iron (“I have often spread out iron for several ostriches and they have not wanted to eat it” 136), and more. He is “a patient observer” (137), keeping tabs on habitats and populations over time to learn their ways. Albert’s network of experts are low- and high-born alike; they are hunters, falconers, fishermen, and even whalers. (He debunks the story of whales so large they are taken by sailors for islands: “Those with experience do not tell such tales” 148). The saint kept his own field notes, and “no creature, however lowly, was beneath his attention.” (151)

Spiders sometimes carry the eggs with them at all times in a little pouch, as does the spider we said lies in wait in a hole in the ground. When it carries its eggs it looks as if it were made up of two globes, one white and one black, for the eggs are very white. Other spiders, however, sometimes keep the eggs in their mouth, sometimes under their chest, and sometimes separate from them. I have personally seen all these ways. (152)

He would make special trips, involve his friends and fellow friars on these natural excursions, and talked with common and noble alike about the natural world.

It is difficult to read Alberts’ works on natural history and not take away a mental image of a Dominican friar squatting in a field, intensely gazing at something passers-by cannot see. Albertus’ curiosity was boundless, and no matter the official tasks at hand, he would invariably take the time to stop and observe the wonders of nature or interview those who knew about them. Many examples of this behaviour have been given above, but adding to these will give a better picture of the scope of the interests the Doctor universalis pursued. (151)

St. Albert’s travels and talk about nature are so extensive that the authors proceed to reverse engineer a picture of what medieval life was like lived in relationship with nature as described in his works. Thus, chapter eight tells of what one can buy at market, animals involved in agriculture and hunting (including all manner of fowl, as well as moose and buffalo), medieval veterinary medicine (especially dogs, horses, and falcons), and even household vermin and pests. We hear of St. Albert’s views of people training monkeys or monkeys training dogs (159–60, 173), and “of dishonest fishmongers who take the heart out of a living salmon and, since they know [its] heart beats the longest outside the body of all fish, place it near the fish for sale, giving the impression that all the fish for sale are equally fresh.” (160)

This fascinating tour of the natural world makes it unfortunate that by comparison the ninth chapter is the longest in the book, discussing human sexuality, gender, and race. Resnick and Kitchell report observations recorded by St. Albert on sexual practices and proclivities, knowledge of sexual anatomy (or lack thereof), and medieval theories on the determination of sex during gestation. They discuss, at great length, the medieval biological view, inherited from Aristotle, of human nature as male by default, and take pains to explain St. Albert’s complexio and four-humours-based theory of race, concluding that “Albertus does not appear to treat whiteness as nature’s default and present in humans naturaliter, whereas he does regard ‘specific’ nature as male and striving to produce other males.” (213)

The tenth chapter concludes Resnick and Kitchell’s tour of St. Albert’s world of nature with a discussion of monsters. St. Albert, of course, would understand by such a term the biological defect or deformity: “Unlike most of his contemporaries, Albertus had a naturalist’s interest in monsters. He was fascinated more than horrified by them and wanted to find causal explanations for their occurrence.” (228–29) The chapter provides the final scene as far as the natural world goes.

The last chapter briefly describes the long and winding road to Albert’s canonization—which occurred only in 1931 by equipollent canonization. The authors discuss the alchemical and astrological content of St. Albert’s extensive corpus—whether truly or falsely ascribed to him—that led some “to incriminate him and even accuse him of practicing magic.” (233) St. Albert overcame such accusations in the long run of history, being declared patron of the natural sciences in 1941. The authors give the last word to Pope Benedict XVI: St. Albert “still has a lot to teach us.”

CURIOSITY OR CONTEMPLATION OF THE COSMOS?

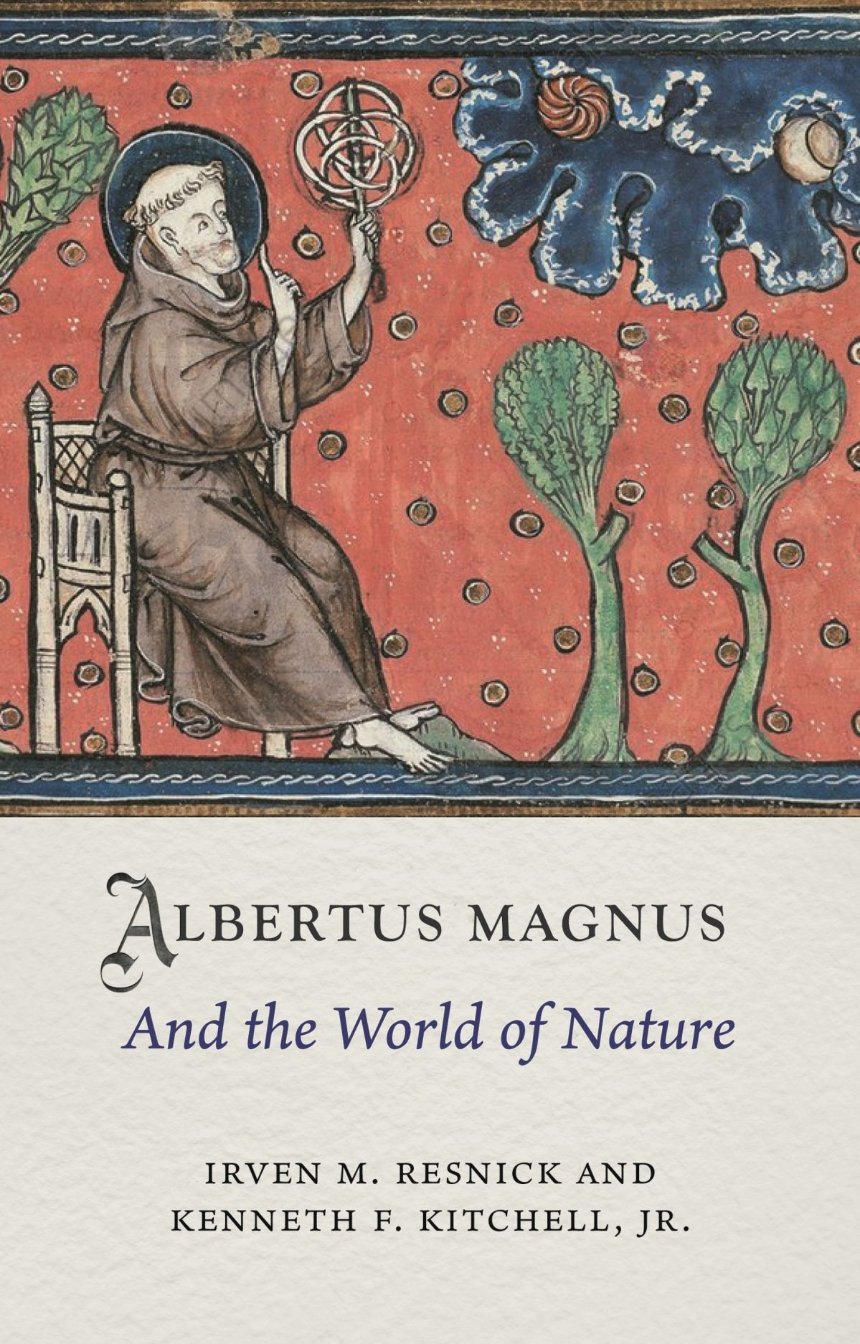

Albertus Magnus and the World of Nature comes with a hearty recommendation for students of the Middle Ages generally and Thomists in particular who want to learn more of the master of their master. The book is lavishly illustrated with color prints of Albertine manuscripts, cathedrals, or medieval bestiaries to convey certain points otherwise difficult to render in words. The notes to the corpus Alberti are collected usually a paragraph or page at a time, a helpful decision given their number, and placed unobtrusively as endnotes (one of the few instances I have appreciated such a decision).

Certain aspects of Resnick and Kitchell’s accounting of St. Albert, however, detract from the overall excellent quality of their book. The opening of the ninth chapter could have done without the insinuation that the saint, having “not merely a prurient interest” in sexual matters (not the “naturalist’s” interest as in other places), broke the confessional seal to report details in this area in his writings (180–81 and n1; see also their Questions concerning Aristotle's On Animals, 454n29 and 411). Writing in generalities does not break the seal. The authors’s treatment of St. Albert’s acceptance of the infamous Aristotelian biological dictum that a woman is “a misbegotten male” appears to slide between distinct senses of the per accidens, conflating what is accidental to nature specifically but not universally with what is accidental to nature in the sense of the monstrous, thus joining with the 16th-century satirists in whose work “the concept of the accidental generation of a woman is incorporated with the other accidents of conception referred to as ‘monsters.’” (Prudence Allen, The Concept of Woman, vol. 2, 79; see ibid., 319) For St. Albert clearly holds that nature’s ends include the female sex for the sake of the continuation of the species.

The point is not to defend unsound medieval biology, but to raise the question whether or not Resnick and Kitchell attend sufficiently to the nature of teleology or final causality in the thought of St. Albert. Indeed, I had hoped for much more of this theme in the book. The order of nature or the cosmos is mentioned, but it is mentioned by the authors most directly in the discussion of the monstrous. Thus, a “monster” in nature is still good insofar as it exists within the overall order of nature (218), and the causes responsible for females to preserve the species St. Albert would trace to cosmological order (234). When the authors discuss teleology (221), they assert that “‘errors’ or defects of nature,” the monstrous, “present the surest proof that nature is directed to a final cause or end.” (my emphasis, citing St. Albert’s Physics commentary, see Borgnet ed., p. 166ff) However, the proof St. Albert discusses in those pages is not his surest proof, but places second. It is a confirmation, a further evidence or clear sign, based upon the prior pages’s discussion of the analogy between art and nature (ibid., 163ff). Indeed, the very notion of a mistake or error is posterior to the insight into nature’s finality or goal-directedness. It seems unlikely that St. Albert makes such a mistake in rating his own articulation of teleology, and for all of the friar’s attention as a naturalist, there is little report of his discussion of the final cause in nature elsewhere. Nor do the authors draw out any connections to St. Albert’s array of evidences “in the order in which he values them” (146) as an exemplary use of Aristotelian dialectic or scientific method.

Indeed, the argument’s focus upon Albert’s attentiveness to nature might miss the forest of the philosophy of nature in the sense of contemplation for the trees of collecting scientific curiosities. Albert’s studiousness is even called “curiosity” in various places. That word has now lost its older sense, as a vice of excessive desire for study and acquisition of knowledge. Perhaps St. Thomas had his teacher in mind when explaining that “if one be ordinately intent on the knowledge of sensible things by reason of the necessity of sustaining nature, or for the sake of the study of intelligible truth, this studiousness about the knowledge of sensible things is virtuous.” We get glimpses and flashes of the sapiential vision of nature which St. Albert pursued through his zealous observance of nature’s order and works, but not more. Perhaps this is a due limitation of the book’s scope. Yet, is it the case that there was insufficient philosophical resolution to the universal diffusion of St. Albert’s scientific mind? “Albertus Magnus,” Dawson tells us, “[was] the most learned man of the thirteenth century and the most complete embodiment of the different intellectual currents of his age.” He it was who “put the whole corpus of Graeco-Arabic thought at the disposal of Western scholasticism through [his] encyclopaedic series of commentaries,” but his strengths lay “in science rather than in philosophy.” (Medieval Essays, 148) Resnick and Kitchell were surely in a better position than Dawson to pass judgment on this point.

The central philosophical lesson Thomists can take from the work is the concrete portrayal of St. Albert employing the dialectical method in his inquiry into nature: from personal experience to the experience of the experts to the sayings of the many and what is heard or reported about nature, and all of this across the entire array of human technological, economic, social, and physical interaction with the natural order under study. This alone affords students of natural philosophy and Thomists alike the chance to see a master at work, and the endnotes tell them where to go for more. Resnick and Kitchell succeed in proving that St. Albert brought into the heart of a Christian natural scientist’s life the words of Aristotle in Parts of Animals, I.5: “We therefore must not recoil with childish aversion from the examination of the humbler animals. Every realm of nature is marvelous: and as Heraclitus, when the strangers who came to visit him found him warming himself at the furnace in the kitchen and hesitated to go in, is reported to have bidden them not to be afraid to enter, as even in that kitchen divinities were present, so we should venture on the study of every kind of animal without distaste; for each and all will reveal to us something natural and something beautiful.”

This review has been updated for clarification.